IPU BLOGGING TASK 2 : FAITH

“Religion, belief and faith identities in teaching and learning” UAL Website.

I visited this page/resource that explores religion, belief and faith identity at University of the Arts London. It is a hub referred to as a “Community of Practice” that brings together staff to share best practice, ideas and experience.

On this website there are several resources that can be used in my teaching as learning materials. There are also three case studies of staff experience in addressing religion, belief and faith at the university. I can encourage my students and colleagues who are particularly interested in this discourse to use this bank of resources.

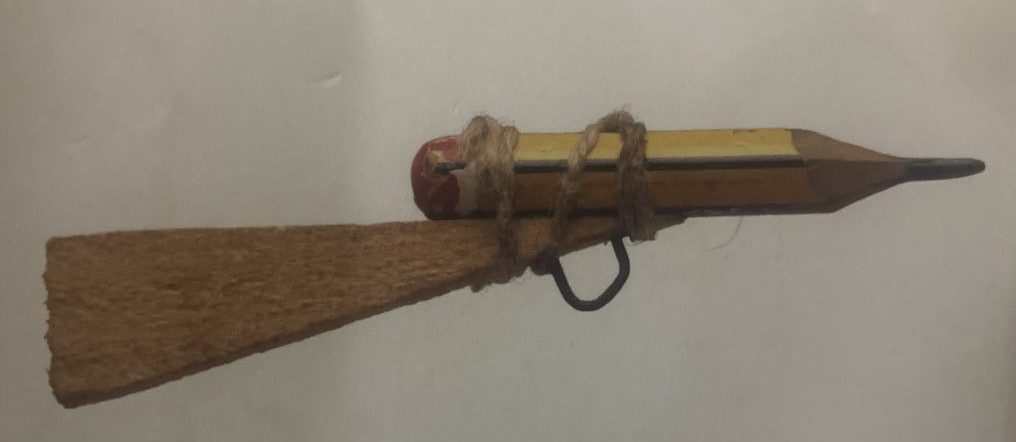

The case study that I will discuss is the “Pen Portraits” icebreaker that was presented by Angela Drisdale Gordon.

Angela Drisdale Gordon is the former Head of Education Office at UAL. She was also previously a course leader for the Foundation Diploma; Fashion Design and Marketing.

The Icebreaker invited students to discuss their personal interests and background in a way that was not intrusive. What made the space nonintrusive was the fact that everyone including the staff was invited to share, but also through the discourses of identity can be sensitive to navigate for all, the questions posed in the workshop were open-ended, optimistic, and relatable. This practice and attitude that hints at the idea of self-actualisation (hooks, 1994) especially in relation to faith, belief, and well-being, seeks to abandon and expose misconceptions and hierarchies in the classroom, and makes the teacher subject again; able and willing to participate in the transformation that is sought for their student. By opening up about her religious belief, she invited others to do the same.

In addition, it is just amazing to see the conversation being had within an arts institution. As someone who was brought up in a Christian home, when faith is seldom discussed in an institution, it gives the impression that the institution is secular and makes one uncomfortable/concerned when speaking about their faith, let alone exploring it within their practice. These are missed opportunities to engage with insights, emerging from different faiths and practices that inform intellectual debate. For instance, debates that explore the idea of image-making Islam/Christianity, and Art History, and possibly finding parallels in the discourse concerning the presence of images of black people in Art history.

Samuel Baah Kortey (Kristo) is an artist, co-founder of the Asafo Black Collective, and member of the blaxTARLINES collective, whose work explores various themes (animal cruelty, theology, myths, etc) drawing insights from religious practices and iconography.

Going back to the notion of “Community”, which the site suggests, doctrines of certain religions e.g Christianity, have always suggested that the religion is practiced within a body – a community, and not in isolation. Even though faith is declared personally, it is practiced communally, and this is a crucial constituent of the religion, that transforms (and translates) it into both a private and public notion (and space). Therefore, within the context of an educational institution, lies responsibility and duty of care, in the provision of needs for faith groups publicly, as well as the recognition of said faith groups being present.

Students’ Unions often have various religious societies that students can join when they arrive at the university. I always refer my students to the student groups that exist at Arts SU and encourage them to create new groups/communities.

References

- b.hooks (1994) Teaching to Transgress: 16 – 20

Religion In Britain: Challenges For Higher Education.

A Multiculturalist Sensibility

Professor Modood introduces the philosophical and sociological notion of Multiculturalism which emerged in the 1960s – a period of independence for many West African nations, the civil rights movements, identity politics of gender, race, and sexuality, and opposition to the Vietnam war and several happenings.

Multiculturalism which considers the notion of plurality embraces and values difference in the society in the struggle for equality. ” This marks a new conception of equality, that is to say, not just anti-discrimination, sameness of treatment and toleration of ‘difference’, but respect for difference; not equal rights despite differences but equality as the accommodation of difference in the public space, which therefore comes to be shared rather than dominated by the majority”. (Momood & Calhoun, 2015)

Multiculturalism had emerged in an era where there was an ideal cultural identity- to fall within that was deserving of fair treatment and to fall outside complicated one’s sense of belonging.

“Finally, multiculturalism as a mode of post-immigration integration involves not just the reversal of

marginalisation but also a remaking of national citizenship so that all can have a

sense of belonging to it; for example, creating a sense of being French that Jews

and Muslims, as well as Catholics and secularists, can envisage for themselves” (Momood & Calhoun, 2015)

The intention is that by way of acknowledging this innate pluralism (whether public or private) our understanding of our “Multicultural” society does not become another stagnant mode of constructing our society. That is to say that, we should not expect our diverse groups to merge into one harmonious culture and as new cultures emerge, they should be valued equally.

I imagine that some may eschew the notion of multiculturalism because it presents the possibility of this delicious, smooth, pureed, pot of soup, where, no tensions lie. I would say it is probably rather, just as delicious as a pot of soup, with roughages, lumps, herbs, and different cuts of vegetables, that will not dissipate into a smooth puree. “This was the stuff of colonising fantasy, a perversion of the progressive vision of cultural diversity” (hooks, 1994)

Should religion be considered a component of racial equality and diversity policies?

This is a very provocative question posed in the foreward.

In a range of contexts, religion can be considered political.

For many of us, religion isn’t simply piety.

For many of us, religion isn’t simply piety, when once upon a time, forts and castles were built to infiltrate certain spaces…

Religion is political for us because traditional religions and customs were repudiated by missionaries and colonial rulers.

Traditional religions and customs were repudiated, and deities abandoned all the whilst adopting new ones.

These adopted practices then become a fundamental pillar of our lives today.

These adopted practices enforced a system of domination.

For many of us, the conception of our religion is a result of our colonial his/herstories.

Our sense of self is also involved with our religion.

Without this, my Uncle Joe would not be found, pouring libation to my ancestors right before reciting the Hail Mary.

So yes, it should be considered as a component of racial equality and diversity policies within an institutional context.

Chinua Achebe’s Things fall apart is a brilliant essay, that explores the impact religion and missionaries had on the Igbo community and customs.

References

- b.hooks (1994) Teaching to Transgress: 30-31

NEW TERMs

- Laïcité – is the constitutional principle of secularism in France. This prohibits the government’s influence /involvement in religious affairs.

Professor Kwame Anthony Appiah Lecture on Creed.

A very interesting and entertaining lecture, which sits amongst a collection of four lectures under the title “Mistaken Identities”. Professor Appiah, opens the lecture by sharing his experience of people encountering his accent and his appearance. He also shares family stories that describe the complexities of his identity, running through his lineage and family’s social circle. By way of doing this, he explores the way our personal stories/ background informs and shapes who we are and our sense of self. He gives examples of personal and shared notions of identity and begins to explore the multiple dimensions of the different “components” of one’s identity – starting with religion.

Professor Appiah also makes the distinction between Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy, and highlights the way we oversimplify the scaffolding of religion, to make it seem like it is a “matter of belief”.

Orthodoxy, he describes as a matter of correct belief and Orthopraxy, where praxy is concerned with practice, action, possibly criticality, and essentially community. This over-emphasis on Orthodoxy, ( the notion of correct belief/faith) often implies a strict adherence to religious script and doctrine. For instance in Christianity, where Biblical texts uphold many racial inequalities, and this is shunned in our post-colonial epoch. Professor Appiah cited the scripture from Ephesians 6:5 and Colossians 3:22 as an example. Therefore, religion can not be simply upheld in this notion(Orthodoxy), as it is complex and is driven by practice and social regulation. I imagine that if the many important social movements and struggles such as the civil rights movements did not occur, many dynamics of power in biblical texts would still be upheld.

This is a great resource I can introduce to my students and invite them to explore how religion intersects with disability, race, and gender, considering their positionality/experience of religion.

Higher Power: Religion, Faith Spirituality and Belief. SoN TOR

Expanding the conversation: Interview with Mark Dean. The Chaplain and Interfaith Advisor for CCW and CSM

A short but dense interview that sheds light on the trajectory of religious institutions in universities in England. Situated in Europe, Mark Dean shares how after the enlightenment and modernist period, tensions arose such that by the 20th century, a common assumption was that western education was secular. This is somewhat evidenced in the kind of art that was being made, where they were shown, as well as who commissioned them. Religious references and iconographies within artworks became subtle, but very much present in the 20th century. Mark Dean mentions that “The post-modern situation is more complicated than this… approximately 50% of UAL students identify as religious and of those who don’t, only a small minority identify as atheist, while most prefer terms such as agnostic, ‘spiritual not religious, etc.

When I was undertaking my first degree, I was aware of the presence of a Chaplain at UAL. However, I was unsure, or at least hesitant to speak to them. I was born into a Christian home and attended many denominations. My father’s family is Catholic and my mother is a Baptist. I did have many questions about my faith, but I was worried that the Chaplain might not understand the complexities of my faith in relation to how I had come to know this faith and my race. Having read the interview, it is warm to see the considerations Mark Dean puts forward, acknowledging the intersectionality at play. I can now imagine, how directing a student to a Chaplain, can support them to enquire, explore, and theorise the complexities of their own religious praxis.

Very reflective and in depth and uplifting analogy . I really enjoyed how you broke professor Appiah’s analogy of religion and identity and most interestingly the interpretation on Bible. One question to ponder, in the end all these beliefs should make us to explore and reflect on our own identity and our religious path rather trying to shape us. I was too fascinated by Appiah’s words and kept on listening to him on other mediums . conversation he makes on race, social class, prejudice and society .

Akussah, I found your thoughts on Professor Kwame Anthony Appiah’s Reith Lecture on Creed in depth and very considered. I had such an emotional response to the lecture series, leading me to question my own faith identity. I wondered if you head listened to the rest of the series? I found how Appiah continues to use analogies to explore positionalities of class, race, religion and how they intersect to be deeply engaging. I liked how you clearly explain the difference between Orthodoxy and Orthopraxy. In the lecture it led me to question if one could be of faith without scripture, practicing with a community but void of a central text. I wondered your perspective on this and if it pushed the boundaries of what faith could be described as being?

Hi Annie-Marie,

Your soup analogy regarding multiculturalism is such a playful spin on words yet an honest recognition of how individual cultures and religious identities should be valued equally within a multicultural society.

I have thoroughly enjoyed reading your blog on faith and the inclusion of your personal beliefs/positionality on this reflective journey.

Religion was not a consideration for me until this unit, but your insight and emphasis regarding religious communities (both in public and in private) … alongside the following resources, has helped me recognise (despite my atheist views) the importance to broaden my existing ‘religious literacy’ (Madood) and my understanding of how religion intersects with racial equality and diversity policies within an institutional context.

I will ensure to add Chinua Achebe’s Things fall apart to my reading list and thankyou again for such an inspiring read.